A Behind-the-Scenes Look at the New York Times “Moment in Time” Project

The latest Hacks/Hackers NYC gathering was all about photojournalism, hosted in the breathtaking Open Plans penthouse (with a wraparound balcony and a fantastic view) on July 27. Jonathan Tepper, co-founder of Demotix, talked about his crowdsourced photo wire based in London, and the team behind The New York Times’ “Moment in Time” discussed their project that mapped 14,000 user-submitted images onto an interactive globe.

Around 70 people attended with a good mix of programmers and content folk. There was a big contingent from Newsweek, which arrived together, and we even had a representative from 10gen, the company which makes MongoDB, the database that was used for the “Moment in Time” project. (He came wearing a MongoDB T-shirt, so was easy to spot)

Moment in Time

Genesis

Jim Estrin, co-editor of the New York Times Lens blog, was driving one day when he came up with the idea of calling on people around the world to take photos in a single moment in time so they could “see what that moment would look like.” The purpose was two-fold: to take photos all around the world and to have a shared group experience. Jim wanted a project that would draw in both amateurs and professionals, which is why he stripped down the rights requests with interesting consequences (more on that below).

“I felt it was an experiment to learn from: how do you do it so large for so many moving parts?” Jim said.

Jacqui Maher was called upon to help with the back end, and Zach Wise — multimedia designer and Flash ninja (if we can still say ninja) — programmed the front-end interface for the front-end.

He debated whether a moment in time was a shared instant (which would have left one third of the globe in the dark at any given time), or a fixed time on the clock that would roll over the world (e.g. “noon on April 30”). He opted for the first and settled on May 2, a Sunday, at 15:00 U.T.C., which was 11 a.m. in New York City. The date was selected because he wanted college students to be able to participate before they got distracted. And the time was selected to minimize parts of the world that would be in the dead middle of the night (though a couple in New Zealand even set their alarm for 3 a.m. to take a photo of the moon). The runner up was the summer solstice, June 21.

To give readers some guidance, they created categories: Religion, Play, Nature and the Environment, Family, Work, Arts and Entertainment, Money and the Economy, Community and Social Issues.

Submissions

From the beginning, Jim predicted the project would get 10,000-20,000 submissions.

“Jacqui thought we were clinically insane and planned for 1,000,” said Jim. To give context, the largest New York Times photo submission project was The Puppy Diaries, which was up for six months and received 4,000 submissions. As Jacqui noted, this ended up being the equivalent of three or four “Puppy Diaries” but submitted within a very compressed period of time. At the peak submission period, photos were getting timestamped to the millisecond, meaning that hundreds of photos were coming in at the same minute. It could have looked like denial of service attack to the servers.

All photos were approved by an editor. Someone of course asked about porn/spam. In the end the team only edited two photos for nudity, and one was intended as a serious submission, but the object covering the sensitive body parts was just ever-so-slightly misplaced.

Front-end

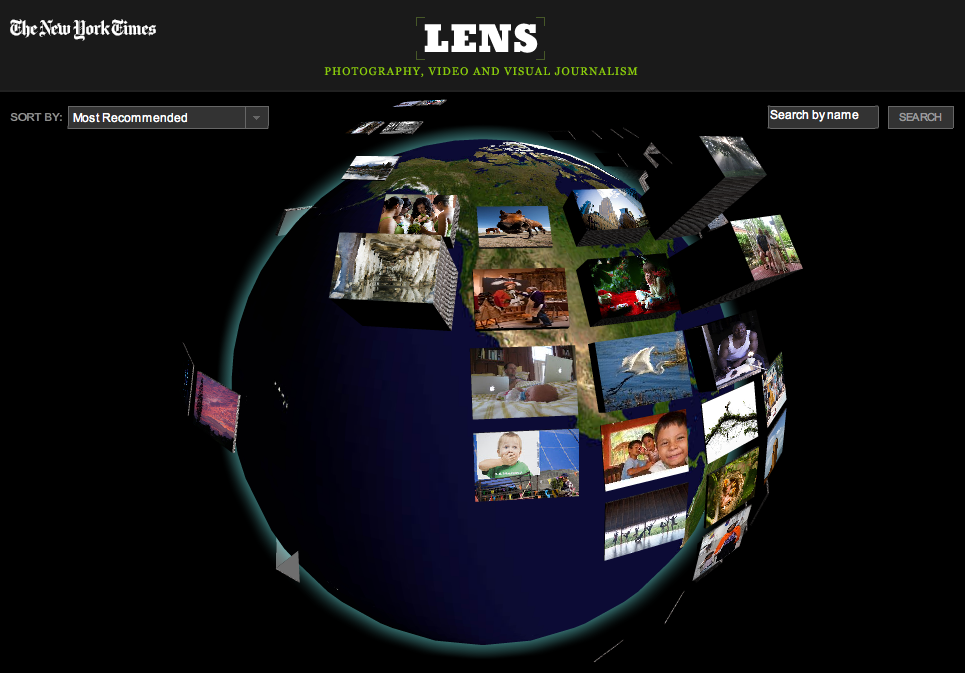

Most of the reader photo interfaces on nytimes.com had been in a “quilt” format. This time Zach designed a globe with the photos sorted into stacks to ease the browsing experience. That way a viewer could dig into a stack and just keep browsing by hitting “next.” He decided to divide the world into a grid that would cluster photos by geography. The upside is that it looked very neat and ordered. The downside of that is where the borders of the grid sometimes landed. For example, photos from New York City and parts of Canada were merged into one stack. For the background of the globe, he ended up using a photo of the earth taken by NASA at that moment. And people would have two points of reference of geography when looking at a photo: the relative position of the earth in the background and the dateline.

Zach ultimately used the Away3D Adobe Flash engine to render the 3D interface. He originally started with Papervision3D but found it too slow and couldn’t handle the number of polygons needed to render the globe. He switched to Away3D which was much smarter about handling polygons, is a newer engine, and ended up being roughly three times faster than Papervision3D in the end.

Back-end

A “Moment in Time” was the first use of the “Stuffy” user submission system, which was an extension and play on “Puffy” (“Photo Uploader Form For You”) originally designed for the Obama inauguration photo album. Puffy was meant as a bit of a one-off, but it had morphed over time to deal with more and more demands. (As Jacqui writes on the Open blog, “We were drowning in multi-screen ‘if-elsif-elsif-else’ blocks, just to determine the look, feel and functionality of each form.”)

So time for a new submission form. This time, they decided to opt for a “NoSQL” database, a.k.a. documented-oriented database, which gave them a lot more flexibility. (For non-techies: we’ve been trying to find a good explanation for a documented-oriented database versus a relational database. The Wikipedia one is improving but not great. But think of the difference between the flexibility a Microsoft Word document gives you to type and add what you want vs. Excel tables which are often pre-defined columns as numbers, currency, date, text.) “We were talking about documents, we weren’t talking about relational data all that much,” Jacqui said.

Jacqui decided to use MongoDB (though she considered CouchDB and Tokyo Cabinet’s Table) in part because the company behind MongoDB, 10gen, was located in New York City. When asked about scaling, she said MongoDB was great. The problems with the project never came from the backend.

Stuffy is built in Ruby on Rails.

Load

Zach himself had a slow Verizon DSL connection in Brooklyn and so he was particularly sensitive to slow connections. Jacqui and Zach tried all sorts of shortcuts to compress the file, but in the end it was still about 500 kilobytes zipped. One shortcut: instead of using the full field names in the JSON data file, they agreed upon single character abbreviations for each: so “s” instead of “submission.” To distract people during the long load time, Zach decided to have the globe spinning in the background, so it looked like something was happening. (This feels somewhat akin to buildings placing mirrors by the elevators to distract people from long wait times).

Lots of questions from all directions from the audience, but no questions on Flash, which raised the question afterwards, “Is Flash over?” That the iPad lacks Flash functionality is deadly in the photo field.

Rights

In order to attract professional photographers to the project, Jim decided to strip down the rights The New York Times would demand for the images — essentially limited to online rights for the “Moment in Time” project, the Lens blogs and some related promotional activities. Readers kept the copyright. The restriction was: “By submitting to The New York Times, you are promising that the content is original, doesn’t plagiarize from anyone or infringe a copyright or trademark, doesn’t violate anybody’s rights and isn’t libelous or otherwise unlawful or misleading. You are agreeing that we can use your submission on Lens, the photojournalism blog of The New York Times, and in the online and print version of the New York Times promoting or referring to the Lens post.”

Later on, he noted this became an issue when someone wanted to archive the photos for historical purposes and the French newspaper Le Monde (whose url always makes me think of “lemonade”) wanted to print 100 of the photos. Whereas Jim did email 100 photo owners for the Le Monde request, it was near impossible to email all 14,000 who submitted for the historical archive.

Outreach

They promoted the project through direct email, on the Lens blog (with follow-up FAQ) and lists. Jim said he spent nearly every night for around six weeks emailing people to alert them to the project. While he was confident that they would get photos from New York, and the United States, he was less confident about other countries.”This was mostly my obsession,” he said. He also set up a Facebook event page. This later on unexpectedly became a place where users (some waiting to submit their photos online) started posting hundreds of photos where others commented on it.

How Much Time Did This Take?

Idea to execution was about 2 1/2 months. That was in part because Jim wanted to get the project done before the end of the school year. In terms of development time, Jacqui and Zach said it was a few weeks of work on their part. However, what was time consuming was dealing with the photos after they came in. Even with six people assigned to approve the photos, Jim ended up pulling an all-nighter (his first since his 20s) to deal with thousands of submissions tumbling in. Also, the administrative interface for approving photo submissions was designed to be accessed by a single photo editor, not six people, so it was excruciatingly slow.

A Photo That Was Outta This World

You never know how people are going to surprise you. The team was thrown a loop when a picture of Mars was submitted from the NASA’s Mars Rover. Zach, who had spent all his time rendering the earth, was briefly panicked that he would have to create another orb (where was Mars at that moment, and where on Mars was the photo taken anyway). ” “I have to put another planet?” he said. The Mars photo generated a good 30-minute debate.

In the end, because the three-piece photo mosaic was assembled at Cornell University, they mapped the photo to Ithaca, New York — which they admit was a bit of a cop out.

Demotix

Demotix launched in January 2009 as a crowdsourced international news photowire with eight employees. The name Demotix comes from the Greek word demos or Δήμος, which refers to “the people.”

Some stats/highlights from co-founder Jonathan Tepper’s presentation, who arrived to speak just off the plane from London:

- Jonathan argued that user-generated content is a bit of a myth. The vast majority content in the user generated sites — Wikipedia, Flickr, YouTube — comes from a very small percentage of very dedicated users who are uploading or making changes. Some people might make an contribution here and there, but that doesn’t mean they will necessarily do it again. It’s the same for Demotix. They have 14,000 registered contributors, 3,000 active ones, but 200 to 300 contribute every day.

- Demotix is built to scale on a variable cost model with low fixed costs.

- They get currently about 25,000 photos a month. Now they have quarter million photos archived, with thousands sold, but high hundreds to print. Print news photo distribution is a bit of an oligopoly and since publications have subscriptions to wire services already, Demotix photos have to be very unique for publications to buy them. Many of the major photo agencies have hundreds of salespeople.

- Some highlights from their photos include the widely distributed one of Skip Gates getting arrested by Cambridge police by neighbor Bill Carter (Bill actually Googled to find how to sell his picture and landed on Demotix) and the shot from the Tehran protests in June 2009 after many foreign press had been kicked out or detained (It ran on the front page of The New York Times under the photographer’s handle “Tehranreporter“).

- Demotix splits revenue 50/50 with the photographers. Rates vary dramatically: images used in an online photo gallery might only cost $5 or $10, whereas newspapers in England for example sometimes pay by the square inch, no matter where it runs in the papers. The Skip Gates arrest photo earned more than $4,000 in sales.

- There isn’t a lot of entertainment coverage despite the fact that there probably is a demand for it, particularly at large festivals which can’t be widely covered. Jonathan thinks that may just be because they didn’t have a lot of entertainment coverage to begin with, and users copy what they see. Given the control that some agencies have accumulated the entertainment/celebrity space, some Hacks/Hackers members thought this had high potential as a market.

- The Web site is built using Drupal. Neither of the co-founders are programmers.

- Demotix is on everyone’s radar now and they are in discussions with all the big players. Are they allies? Competitors? Frenemies? It’s hard to say. Demotix turned down an chance to be acquired earlier on after seeing what happened to Scoopt, a crowdsourced photo service which was bought by Getty images in 2007 and then shut down in 2009.